Chancellor defends income tax freeze and salary sacrifice limit

The House of Commons Treasury Committee held three post-Budget hearings in the two weeks following Budget 2025, meeting with the Office for Budget Responsibility, economists and the Chancellor and her officials, and questioning them about the Budget process, the public finances and the measures announced on 26 November.

This report focuses primarily on witnesses’ comments on the Budget tax measures.

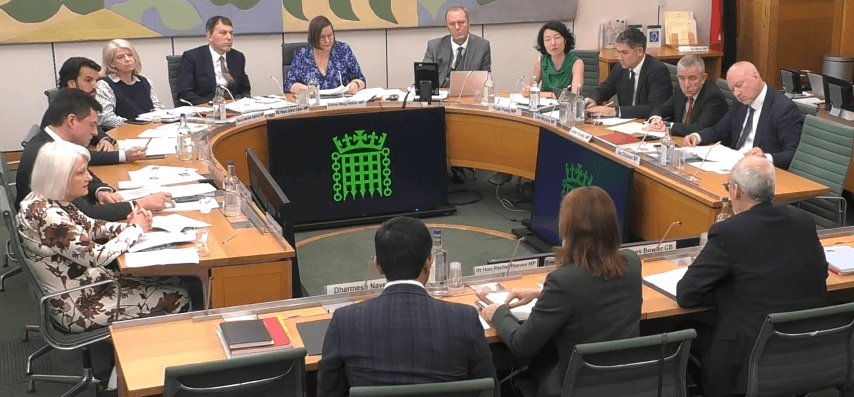

Session with the Chancellor and Treasury officials – Wednesday 10 December

Witnesses

- Rt Hon Rachel Reeves MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer

- James Bowler CB, Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, HM Treasury

- Dharmesh Nayee, Director of Strategy, Planning and Budget, HM Treasury

At the beginning of the session, the Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, acknowledged there were “too many unauthorised leaks” ahead of the Budget, stating that “I want to state on the record how frustrated I am and have been by these incidents and the volume of speculation and leaks”. She added that a leak inquiry is underway, and the government is also conducting a review of the Treasury security processes to inform future fiscal events.

Income tax and threshold freezes

On the government’s approach to income tax following the press conference on 4 November, John Glen (Con) said: “The clear impression left by the scene-setter press conference… was that income tax was going up… and then 10 days later it was not. What can you tell us about your decision-making process during those 10 days”.

The Chancellor responded that, in her speech on 4 November, “I was very clear that everyone would have to make a contribution, and you saw that in the Budget on 26 November: we froze, for an additional three years, the tax thresholds”. She argued that “that is not a breach of the manifesto, but it is asking everybody to contribute more”.

Reeves further highlighted measures to cut inflation, NHS waiting lists and reduce debt and deficit, adding: “We would need to build more fiscal resilience—which we did by taking the headroom to £21.7 billion—and that we would have to ask everyone to contribute.”

Asked why the decision to raise the rate of income tax was reversed, Reeves explained: “The Prime Minister has been clear that was one of the things that we looked at, but we were also looking at the tax thresholds. In the end, because of the decisions we made on higher value council tax, property, dividends and a number of other measures, we were able to keep the contribution from working people as low as we possibly could.”

The Chancellor confirmed the decision was taken jointly by her and the Prime Minister saying they had “met two or three times a week during the Budget process… We decided it together, as a team.”

Glen challenged Reeves on reconciling her Budget statement with manifesto promises, pointing out that she had promised that “there will be no extension of the freeze in income tax and national insurance thresholds”. In response, the Chancellor said: “Our manifesto was clear; it referred to the rates of income tax, national insurance and VAT. But I have been very clear… that everyone makes a contribution through freezing those thresholds.”

On whether threshold freezes are less progressive than raising headline rates, Reeves stated: “I do not recognise that. I think they are broadly similar.”

Salary Sacrifice

The Chancellor defended changes to salary sacrifice saying that, left unchecked, the cost of salary sacrifice would go up by three times in the next few years. “We already spend £70 billion a year on pensions tax relief… Salary sacrifice was only ever really expected to top up pensions, rather than being the main vehicle.”

The Committee chair, Dame Meg Hillier (Lab), asked if the pension was the particular focus, as there are salary sacrifices for other things such as gym membership, extra holidays etc, to which Reeves replied “No, the focus on this was around the tax treatment for pension savings”. She emphasised: “You can still put £2,000 in and have exactly the same tax benefits as you previously had, but any contribution over £2,000… will get the pension tax relief, but not the additional salary sacrifice relief”.

Business taxes

Luke Murphy (Lab) asked about changes to capital allowances. Reeves explained: “What I did at the Budget was to decrease the main rate of write-down allowances—just the main rate—by four percentage points to 14% from April next year. That has allowed us to fund a new first-year allowance while also raising revenue to protect public finances.”

Reeves continued that what the government is trying to do is introduce more generous up-front relief for investments, including for some of the leasing of equipment and machinery that is not eligible for full expensing. Murphy pointed out that the first-year discount does not apply to second-hand assets, but only to leasing. Reeves agreed there was more to do, in a range of areas, including that one and also around intangibles.

Dame Harriett Baldwin (Con) reminded the Chancellor of her statement in the Budget that: “The high street will benefit from permanently lower business rates for retail, hospitality and leisure”. She compared that to the reality that “pubs are facing a 15% rise, and there are music venues… with a 431% rise… Would you accept, Chancellor, that a lot of these businesses feel misled by that statement”.

Reeves explained that there were two things happening at the same time: a revaluation and a permanent lowering of business rates.

Baldwin cited UKHospitality, which thinks there will be a 15% increase on average pub and asked the Chancellor to look at this matter again. Reeves said “Fifteen per cent is the cap. That is the highest it can be.” She suggested the average rise for pubs would be 4%.

Financial education and tax reliefs

Dame Siobhain McDonagh (Lab) inquired about more financial education in schools. Reeves said that “as part of the financial inclusion strategy… we are introducing… better education on budgeting and saving”.

On tax relief evaluation, a question asked by Bobby Dean (Lib Dem), the Chancellor said: “We have done some really good work on cracking down on tax avoidance and closing loopholes… while there is a gap between the tax that is due and the tax that is paid, there is more work to do.”

Tax on wealth and asset income

Yuan Yang (Lab) asked about narrowing the gap between tax on assets and work. Reeves said: “What I did in the Budget was to increase by 2 percentage points the basic rates on dividend, savings and property income… I think we got the balance right.”

Yang further pressed on whether there is space for more narrowing, to which the Chancellor replied: “Obviously, if you go out to work, you pay national insurance, and you do not pay national insurance on other forms of income, but we have taken action in this Budget to narrow the gap between those different forms of income”.

Indirect taxes and duties (EVs and gambling)

Jim Dickson (Lab) asked about Electric Vehicle excise duty, suggesting that the levy will bring in “only about a quarter” of what fuel duty brings in. Reeves replied: “We have set the level of eVED at half the rate we get from fuel duty… We have no plans to increase it further, and we would not do so until the move to electric vehicles is well secured.”

Reeves also outlined the rationale for higher online gambling taxes, saying: “There is plenty of evidence that online gaming… result[s] in more serious harms than in-person betting. That is why we chose the package that we chose… A theme running through the Budget was that high streets should not be undercut by online.”

She additionally acknowledged potential industry restructuring but said: “These taxes apply whether the company is offshore or not, because it is a tax on the bet.” She believes that the government are right to “tax it more appropriately and have a level playing field between the high street and online businesses”.

Session with the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) – Tuesday 2 December

Witnesses

- Professor David Miles CBE - Member of Budget Responsibility Committee at OBR

- Tom Josephs - Member of Budget Responsibility Committee at OBR

The previous week the committee had heard from the two remaining members of the OBR’s Budget Responsibility Committee, following the resignation of the chair, Richard Hughes, a few days earlier.

The session started by touching briefly on the event which had led to Hughes’ resignation, the early publication of the OBR’s Budget document. This was followed by a longer set of questions about the information leaked by the Treasury in the weeks running up to the Budget and the process and timings by which the OBR’s forecasts were produced. This fed into questions put to the Chancellor the following week (see above). Towards the end of the session the OBR’s calculations on the Budget measures were explored.

Gambling taxes

Asked about the complexity of scoring gambling tax changes, particularly regarding behavioural shifts and the risk of migration to the black market, Tom Josephs said he considered it “a complicated measure to cost”, suggesting that “the changes create quite a number of different rates across different forms.”

He believed that operators would pass on the cost of the tax increase to their customers, which could lead to a reduction in demand and reduce the yield from the measure by a “reasonable amount”. He added “that does build in some behaviours of people moving into the illicit market”, although evidence from other countries shows that if a well-regulated gambling market is in place “the opportunities to do that are relatively limited, and generally people do not want to do that if they can, because of the obvious risks involved.”

EV and fuel duty

On the new tax on electric vehicles and its effectiveness in offsetting lost fuel duty revenue, Josephs replied: “We have for a long time flagged in our long-term risks report the big risk to government revenue from the loss of fuel duty over time”. He provided their analysis that the new levy will offset “around a quarter of the lost revenue from fuel duty over the long term.”

On the impact of the levy on EV sales, he said: “There is the actual new charge on electric vehicles, and the impact that has on purchasing decisions, there are the offsetting policies that the government have introduced to try to incentivise purchases through grants and other changes to taxation, which will reduce costs”. He predicted that the overall sales of EVs would be about 100,000 lower than they otherwise would be.

Asked how much headroom the government would lose if it did not go ahead with uprating fuel duty by the Retail Price Index, Josephs replied that their estimate of the cumulative cost since 2010 is about £120 billion, adding “in this forecast, if those rates were not uprated, it would cost about £3.5 billion a year.”

Dividends, non-doms and salary sacrifice

In relation to the behavioural effects of tax increases, in particular on dividends, Josephs said: “I think that reflects the fact that it was a relatively small increase. It applies just to basic and higher rate taxpayers and not to additional rate taxpayers. I think that quite a lot of the dividend taxes will be paid by additional rate taxpayers, so that is essentially why there was not a huge amount.”

The committee highlighted that there are many anecdotes about wealthy people leaving the country, asking “is there any fact-based information that would change any of your [OBR] information”. Josephs responded: “we have not changed that assumption because we do not feel that there is any hard evidence that would lead us to change it”. He added that they would have hard data by early 2027, “when we start to see the actual tax receipts.”

Asked if the Budget’s salary sacrifice measure would have a long-term impact on OBR medium-term fiscal forecasts and the amount that is saved for pensions in this country, Josephs said: “You would expect it to have an impact over the long term. It reduces the tax benefits of the salary-sacrifice route to pension saving, and over the long term… you may expect lower pension savings than you otherwise would have done.”

Impact on growth

Asked whether the measures announced in the Budget would improve growth, Professor David Miles said: “No, in the sense that we did not judge that the positive effects outweigh the negative effects. I think it is in some ways not surprising that the answer is no, because if you are going to take the tax take out of GDP higher again… it is very difficult to raise taxes without affecting incentives to save, to work, to invest, to become an entrepreneur and to stay in the UK. It is very difficult to do that without having some negative effects”.

Session with economists – Wednesday 3 December

Witnesses

- Professor Tera Allas CBE, Chair of Advisory Committee, The Productivity Institute

- Helen Miller, Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies

- Ruth Curtice, Chief Executive, Resolution Foundation

- Dr Peder Beck‑Friis, Economist, PIMCO

The day after questioning the OBR, the committee heard from a panel of economists.

Tax policy design and speculation

Asked whether the Budget speculation had led to behavioural shifts, Professor Tera Allas said: “I would be quite moderate about attributing any sort of impact in the real economy to the speculation. However, looking ahead, she warned: “if it becomes a repeated pattern, it will keep dragging down the reputation of the UK as a place to invest”.

Ruth Curtice distinguished between two types of speculation: forecast information and speculation about specific tax measures. “The question there is whether we want to revert to a process that is more secret or whether we want to go to a process that is more transparent”, she continued. While considering the current middle ground “unsatisfactory”, Curtice argued that speculation about tax measures arises from low fiscal headroom and manifesto tax locks, making it difficult to reconcile both. She also believed that in this Budget the Chancellor did not “give a sense of where she would like the tax system to go in the future in a way that might help constrain that speculation”.

Helen Miller emphasised that effective tax policy design should begin “with that vision piece.” She believed that the UK tax system policymaking is “not awful” but “could do better”. On whether ‘kite‑flying’ is a legitimate tool or there is a need to look at the whole process around tax policy, Miller noted: “If a politician wants to test the water or fly a kite, it comes at a cost. People might change their behaviour as a result.”

Distributional impacts: threshold freezes vs rate rises

On whether the Budget was progressive, Curtice judged: “It was a redistributive Budget… The tax rises… are progressive.” She added: “when we think about the tax changes… a broad-based tax measure on income tax will always affect a range of households”. A rate rise would have been marginally more ‘progressive’ than the threshold freeze, she suggested.

Miller thought that rate rises would have been “much more progressive” than broad threshold freezes, especially given personal allowance tapering at the very top. Asked if the government need to go for much more comprehensive reform, rather than just adjusting rates or changing the base each time, she replied: “You take two people who are both in the top 1% or 0.1%. They can be paying very different tax rates depending on how they get their income… That is where we really need the system‑wide reform.”

Business taxation

On the ‘permanently lower’ rate of business rates, Miller cautioned against misdiagnosing rates as the high‑street’s core problem and highlighted incidence on landowners over time: “I would expect… that to be reflected in rents and, basically, to be a giveaway to landowners.” “We need to… move towards a land value tax… and take the value of the property out of all the tax.”

On changes to Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) and Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS) limits, while Allas described them as likely to have a “positive effects”. Miller observed they are “part of the tax system that is complex and changes a lot”. Additionally, she recommended that instead of taking these schemes and ‘tweaking them a bit’ around the edges, it would be better to consider whether “we… need this many schemes” and “when do you want to give tax relief”.

Electric vehicle (EV) tax and road pricing

The panel welcomed action on EV taxation but expressed concern about the design. Miller said: “The fact that it is a flat tax of 3p per mile means that it is not very well targeted at congestion.” She argued for a congestion‑related instrument to replace declining fuel‑duty revenues.

Allas warned of path‑dependency, stating: “It could be a slippery slope if we have now gone for the 3p per mile, which is too low and is not related to congestion… If this is now taken as, ‘we have solved the problem’, that creates a future problem that is even bigger.”

Asked if the government missed an opportunity to introduce a more ‘comprehensive’ road pricing system rather than just have a new tax, Allas agreed: “It needs to be more targeted in the sense that it targets the costs”.

Salary sacrifice

The changes to salary‑sacrifice triggered debate over distributional burdens. Curtice confirmed that those who pay the highest national insurance, which would be those earning between about £10,000 and £50,000, would be most affected (in terms of the marginal rate). For typical contribution levels, she noted the cap’s reach: “If someone is making the standard 5% contribution, they would have to earn over £45,000 or £46,000 in order to be exceeding that £2,000 cap.”

Miller added: “32% of contributions are made by individuals who earn more than £100,000… the overall distribution will be highly progressive.” She also acknowledged that “lots of people who are in that basic rate bracket will not be making enough contributions to be over the £2,000.”

Non-Dom regime and tax on wealth

On the non‑dom changes, Curtice described them as “a small tweak” and emphasised uncertain behavioural responses: “It is not yet clear whether the number of people leaving… is higher or lower than what the OBR had already assumed.” Miller also called for richer longitudinal data saying: “You want to know when they came… how much they earned… who is leaving… the compositional effect will matter a lot.”

On taxing wealth more effectively, Curtice highlighted the lack of detailed data for the top 0.1% and suggested that the Budget could have better targeted the wealthy. She provided an example that “the taxation of partnerships is something that was speculated about and then not included in the Budget. About 70% of income from partnerships goes to the top 1%”.

Miller agreed and said a comprehensive distributional analysis should consider how the Budget impacts different groups. “We should also remember that any given Budget is having a tiny effect compared to the £1.3 trillion… we already raise in tax. If you look across a longer period, it has been the case that many governments have been increasing taxes at the top, and at the top by much more than other places”, she stated.